The Animation Time Machine has just returned from its latest mission to the year 1924, gathering snippets of animation news from exactly 100 years ago!

It’s awards season again! So, what news does the Animation Time Machine have about Hollywood movie awards in 1924? The answer is … none!

It’s no surprise. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences wasn’t formed until 1927. The first Academy Awards ceremony was held two years after that. Wondering which animated film came away with the prize that year? Forget it! In a ceremony at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel in Los Angeles in May 1929, it took the Academy just 15 minutes to hand out awards in a dozen categories … and animation didn’t feature at all.

This got us thinking: Just how important was animation to American audiences in the early years of the 20th century? We sent the Animation Time Machine back through the temporal vortex to find out.

One hundred years ago, your average movie theater was typically offering a two-hour variety show. There was a main feature (a five- or six-reel drama running for no more than 90 minutes) plus a grab-bag of shorts. These might include a newsreel, a comedy, documentaries of educational or scenic interest and, you guessed it, a cartoon. And remember: all these movies were silent, exhibited with live musical accompaniment.

In February 1924, the trade journals were lively with debate about the relative merits of all these items. Despite the growing popularity of 12-reel ‘super-feature’ epics like The Sea Hawk0 or The Thief of Bagdad, most commentators agreed that audiences still craved variety. Guy Price of the Los Angeles Evening Herald summed it up:

“The ‘short subject’ is all-important to the theater program. It is the ‘relief’ so often needed. People go to a picture theater for pictures and they expect to see a variety. The ideal bill is a dramatic feature, comedy and education of a light dramatic feature, a light comedy and something of an educational or semi-serious nature.”

By 1924, animated films had certainly become a popular part of this variety act, but their inclusion in the program wasn’t guaranteed. Here’s Harold B. Franklin, director of theaters at the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, writing in The Film Daily in February of that year: “Cartoons are interesting and amusing but we do not as a rule play cartoons when a comedy is provided for a program, as we find that a comedy and cartoon have much in common.”

In this rather conservative climate, American audiences expected their animated films to conform to a certain stereotype. Specifically, they wanted to see hand-drawn characters engaged in amusing antics.

Imagine their reaction when something completely different arrived from the other side of the world.

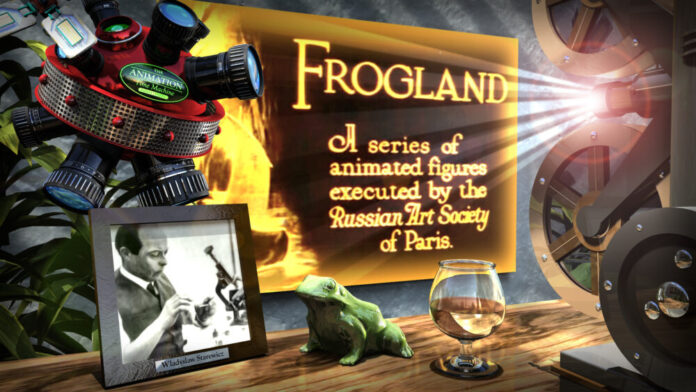

In February 1924, the industry journals began reviewing a stop-motion short called Frogland. It was the work of Polish-Russian filmmaker Wladyslaw Starewicz, whose 1910 short film Lucanus Cervus is widely regarded as the first of its kind to feature animated puppets (actually, dead stag beetles with articulated wire legs).

Early in his career, Starewicz made some 24 animated films in Moscow, working with Russian movie pioneer Aleksandr Khanzhonkov. Fleeing his homeland after the 1917 October Revolution, he joined other refugees in Paris to form the Russian Art Society. Locally, he went by the name Ladislas Starevich. It was in Paris that he made Frogland, (this time using fabricated puppets rather than deceased insects).

Frogland is based on Les Grenouilles qui Demandent un Roi (The Frogs Who Desired a King), a 1668 fable by French writer Jean La Fontaine. Released in the U.S. by the Fox Film Corporation on January 20 , 1924, it’s a cautionary tale about a tribe of frogs who are disgruntled with their king. When the frogs ask Jupiter to step in, the mischievous god transfers the throne to a hungry stork, who promptly eats the hapless pond-dwellers.

American reviewers immediately fell in love with this innovative stop-motion film. Moving Picture World called it “… an exquisite exemplification of the plastic art … In detail it is so perfect that gazing at the film one is actually impressed that live frogs are enacting the roles.”

The Film Daily positively gushed: “Russian Refugees in Paris, known as the Russian Art Society, have made one of the most interesting novelties to come to the screen. It is claimed that it took nearly two years to complete this short subject and it can readily be believed upon viewing the offering. It consists of the genuinely artistic miniatures of frogs with a highly imaginative background representing the frogs’ domain at the bottom of a pond. The lighting, the movements of the carefully constructed frogs and the colorful settings are indeed extraordinary.”

Glowing reviews, to be sure. But how did Frogland go down with American audiences who, in that very same month, were splitting their sides at Felix Crosses the Crooks, in which their favorite cartoon feline teamed up with a friendly elephant to foil some dastardly bank robbers?

The answer is ‘not so well.’ In February 1924, Exhibitors Herald published feedback from movie theaters around the country. “Sold as an out of the ordinary, special single reel,” said the owner of the Grand Theater in Anamosa, Iowa. “May be so, but our customers did not care for it. Leave it alone.” The owner of the National Theater in Graham, Texas, was even more scathing: “Sold to me as a comedy. My bunch couldn’t see it at all. Pronounced it a piece of cheese.”

All of which goes to prove that some things never change. A film that charms the critics — and which, over time, acquires status in the annals of cinema history — won’t necessarily go down well with your average Joe. Wladyslaw Starewicz is now regarded as one of the great pioneers of animation … but that didn’t stop a certain Texas theater-owner-of-the-day calling him a cheese-monger!

Join us again next month when we dispatch the Animation Time Machine on another mission, back through the decades to March 1924!

Win a Funko X Lilo & Stitch Prize Pack!

Win a Funko X Lilo & Stitch Prize Pack!