|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

[adrotate banner=”1026″]

“Animation is an art form that’s removed from reality.”

— René Laloux

Simple yet complex, fantastical but real, savage and gentle — René Laloux’s award-winning films remain a huge inspiration within the field of animation. La Planète Sauvage (Fantastic Planet), which was released on December 6, 1973 (after premiering at the Cannes Film Festival earlier that year), not only showcases a decade’s worth of artistic exploration and refinement but is a definitive masterwork. Aside from the hugely influential Métal Hurlant (Heavy Metal) magazine that would hit newsstands the next year, such hallucinogenic and effervescent concepts have only been hinted at since then in the universes of Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind; the biopunk concepts of Image Comics’ Prophet and Prism Stalker; and the 2019 animated short Scavengers, which spawned a new series, Scavengers Reign, on Max.

But understanding the unique nature of Fantastic Planet is to understand René Laloux’s attitudes and sensibilities. This is hugely important to not only grasp the human qualities of the film, but also the processes he learned working with other artists — all of which brings to light the impact and timeless nature of this animated space oddity.

A Strange Story

Based on the 1957 novel Oms en série (Oms in Series) by Stefan Wul, Fantastic Planet tells the story of the Oms who have been enslaved by a giant alien race known as the Draag. There are similar threads to what Pierre Boulle would reveal in his 1963 novel, Planet of the Apes, the Oms’ Earth origins revealed via the Draag’s telepathic documentation of “Terre” (the French word for Earth; “Oms” is similarly a cognate of hommes, meaning men or humankind). Wul’s mythology and poetry is a major part of what still helps to distinguish the film from most that have succeeded it over the past 50 years; the whimsy and operatic nature often feeling like a strange interplanetary documentary.

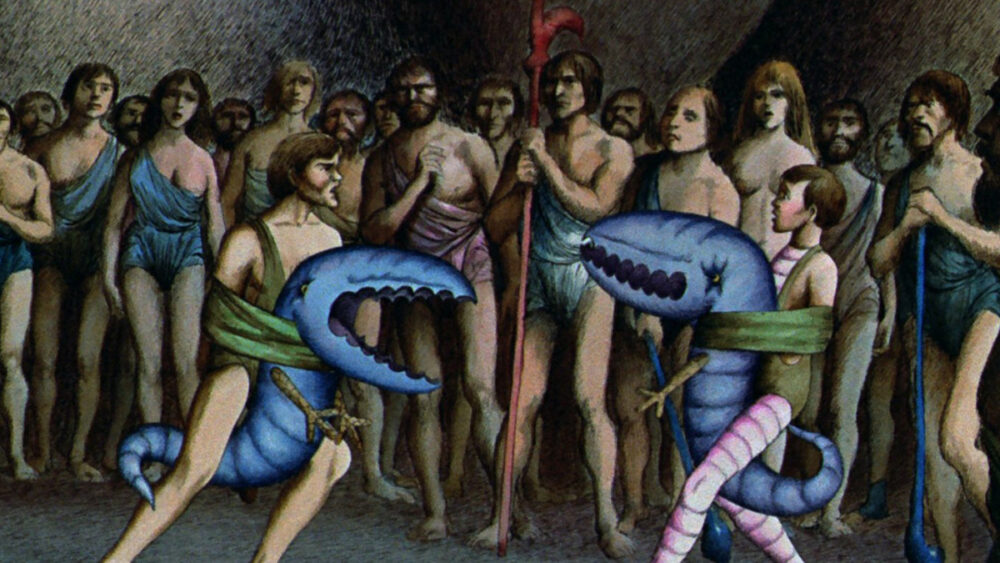

With no shortage of shocking moments, the contrast of sadism and playfulness is seen from the outset as the Draag offspring repeatedly flick an Om mother (carrying her newborn) to the ground before she is dropped to her death. As cold as they are blue-skinned, it is hard to define between casual mistreatment or blind cruelty. Yet what is clear is that the audience sympathizes, as we are immediately shown the fear, distress and vulnerability of a (fragile) mother; the surviving Om child, “Terr,” becoming no more than a curious pet. Although some remain domesticated — stroked and caressed by adult Draag between meditations — the more “savage” Om, who live among giant flora and skeletal alien remains, are exterminated every two Draag years (the equivalent of 90 Earth years). This is an allegorical tale shaped by the savagery and curiosity of humanity.

Technique and Process

Accompanied by Alain Goraguer’s psychedelic moon safari orchestration, this hallucinogenic journey boasts a distinct tactile quality that evokes Laloux’s early days as a woodcarver. When Laloux found his calling as a counselor at the groundbreaking La Borde psychiatric clinic in Cour-Cheverny, he used his practical skills to assist with art therapy, which was revolutionary at the time, and worked with patients on shadowgraphs inspired by his interest in puppetry and animation. He captured the first document of his teachings in a 66mm black-and-white film, Tic-tac (Tick-Tock), in 1957, a human experience that the patients developed themselves through animation; and a crucial collaboration that helped to establish Laloux’s cutout approach. Collaboration with his patients continued, resulting in what is considered to be his directorial debut, Les dents du singe (The Monkey’s Teeth), in 1960.

It was through Laloux’s psychiatric work that he met Fantastic Planet‘s co-writer and production designer, Roland Topor. They would work together on a number of short films, most of which reflected the collective trauma that lingered in the aftermath of World War II. Such ills are highlighted in their first work together, Les temps morts (Dead Times, 1965), which displays the ravages of war, presented as an animated assembly of stock footage, photographs and engravings. The narration spills forth — “The world is a vicious circle” — furthering their themes of madness and despair.

Although not as explicit and documentarian as this earlier short, Fantastic Planet carries all the hallmarks of childlike innocence juxtaposed with violence and horror. The visual style Topor gave seed to often resembles a perverse nursery rhyme — like the apocalyptic invasion of giant mollusks in Les escargots (The Snails, 1966) — coupled with heavy influences from Lotte Reiniger, Henri Gruel and Jan Lenica’s cut-out style. On top of its Edward Gorey vibes, obviously Python-esque parallels can be made to Terry Gilliam’s animated comedic interludes, along with Walerian Borowczyk’s early animated works.

This was a period that saw an infinite wealth of ideas between the two men: a meeting (and eating) of minds. However, Topor’s talents went way beyond his surrealist influence and distinctive illustration work, exploring paranoia and lunacy in his 1964 source novel for Roman Polanski’s The Tenant (1976), and playing Renfield in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979).

Style and Substance

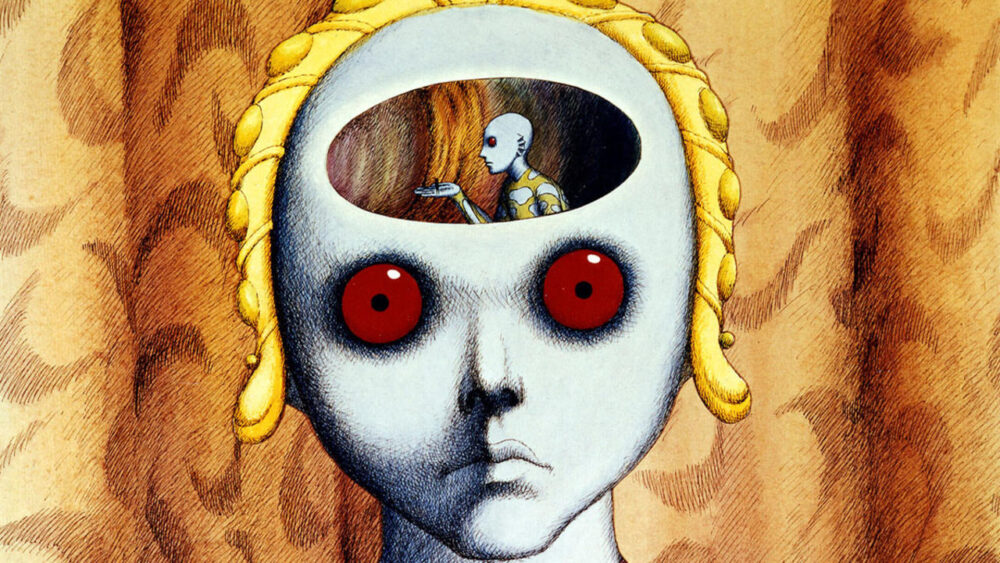

Beginning production in 1968 — most of which took place at Jiří Trnka Studio in Prague — Topor’s commitment went as far as adapting the novel and working on the original concept art before Czech artists Josef Kábrt and Josef Váňa built on the world further. While Váňa worked on the backgrounds, Kábrt not only developed the character designs but also, as an animator, (instinctively) oversaw the techniques and processes that Laloux and Topor had already mastered. Understanding the evolution of Laloux’s earlier cut-out techniques — especially via his collaborations with Topor — proves how important style and technique have become over the years in distinguishing such works.

The legacy of Fantastic Planet also lies in its ability to be read into. Topor, Kábrt and Váňa’s visuals make it closer to studying an etching or surrealist masterpiece, and the static nature of the animation focuses on strict composition and framing that feed into the symbolic and metaphorical aspects of the film.

‘Fantastic Planet is a film that showcases the extreme contrasts of human nature; the core narrative is all about the importance of learning. However, far from the prosaic, there is also an ethereal quality and arcane dignity at the heart of this deranged, alternative world.’

Of course, there are the more literal elements too, such as the phallic spacecraft illustrating the Oms’ generative power as they manage to escape and repopulate during the film’s final moments. Yet, overall — due to its experiential approach — it manages to avoid any of the cliches we would associate with most science fiction and instead presents a more dignified and liberating experience through a moral message.

Looking at these details more closely, while keeping in mind Topor’s inspired “Rabelaisian” style, there is a class and racial allegory at play. Wul’s story descended from François Rabelais and Jonathan Swift’s tradition of satire. During the final act, a fallen Draag reminds us of a bluer (and bloodier) Gulliver pinned by the Lilliputians, and the “de-Ominisation” eerily evokes imagery from the Holocaust as the free-living Om are gassed and squashed like ants, their tiny corpses littered about the undergrowth as their oppressors — gas-masked Om with hounds at hand — continue their genocide.

Fantastic Planet is a film that showcases the extreme contrasts of human nature; the core narrative is all about the importance of learning. However, far from the prosaic, there is also an ethereal quality and arcane dignity at the heart of this deranged, alternative world with Laloux’s humanistic sensibility still shining through; the caretaker refuses to accept man’s ignorance and animosity, in the hope that we continue to inform ourselves and understand each other through peace and coexistence.

Fantastic Planet is currently available to stream on Max, Amazon Prime Video, YouTube, Google Play Movies & TV, Vudu and Apple TV.

Rich Johnson has written for many publications, including Fangoria, Little White Lies, The Digital Fix, Shots, Rue Morgue, Eureka and 101 Films. A lecturer in graphic design and film studies, he also delivers various cinema courses including BFI masterclasses. richpieces.com | @richpieces