***This article was written for the March ’25 issue of Animation Magazine (No. 348)***

Audiences associate the films of Studio Ghibli with their evocative depictions of nature: the summer rainstorm in My Neighbor Totoro, the forest ruled by the Deer God in Princess Mononoke, the woodlands that the tanuki (Japanese raccoon dogs) fight to save from bulldozers and concrete in Pom Poko.

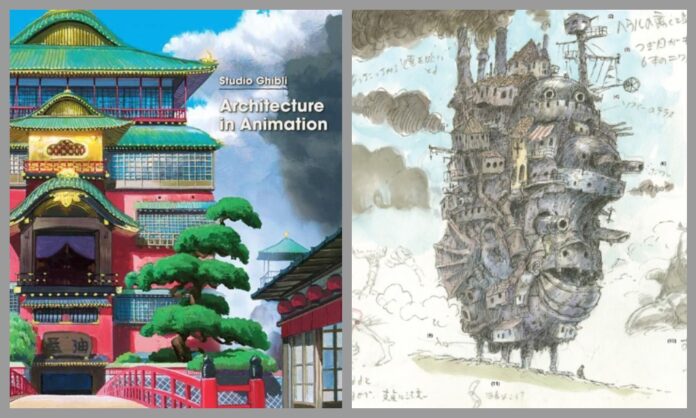

But, a new book available for the first time in English instead looks at the man-made beauty of the buildings seen in the studio’s beloved movies. In Studio Ghibli: Architecture in Animation (VIZ Media, $35), readers are invited to discover the history and thought behind Ashitaka’s village in Princess Mononoke; the arrangement of the rooms in Seiji’s grandfather’s house and Shizuku’s family’s apartment in Whisper of the Heart; and the formal Heian-era gardens and palaces in The Tale of Princess Kaguya.

Most of the text is a sort of dialogue between Hayao Miyazaki and Terunobu Fujimori, a noted architect and director of the Edo-Tokyo Museum. Each comment is marked with a small caricature: Fujimori with neatly parted hair and glasses; Miyazaki as his trademark pig, now sporting a bristly white mustache.

Reflections of the Residents

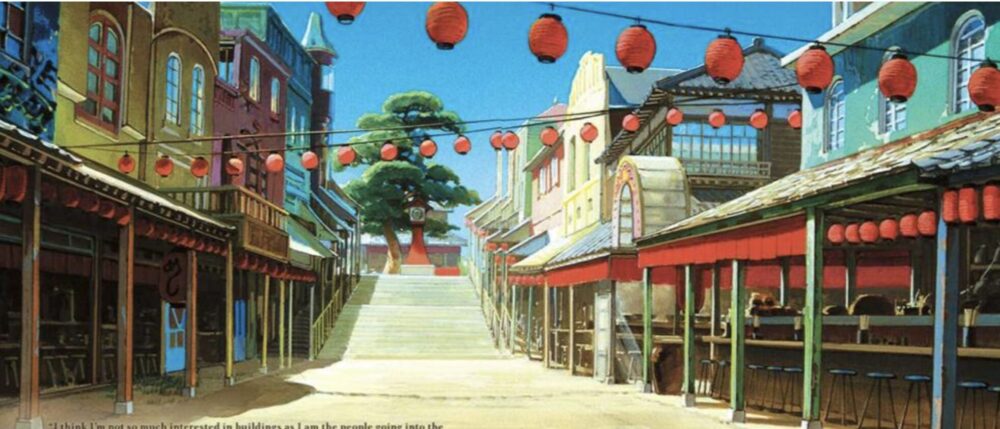

Miyazaki and Fujimori examine questions about structures in the films in different but complementary ways. As the founder of the Architectural Detectives group, Fujimori wrote about the kanban-kenchiku (billboard architecture style), which was built during the push to modernize Tokyo during the Meiji era (1868-1912).

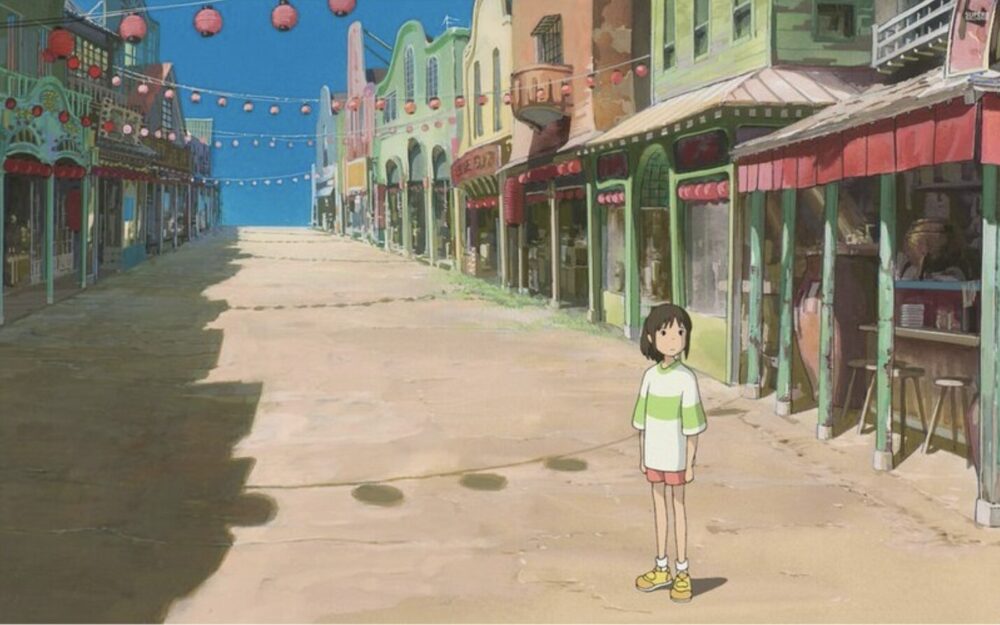

Miyazaki explains that’s he’s less interested in buildings than the people who inhabit them. He imagines the history of a decrepit kanban-kenchiku shop with a cheap sign that stands among the restaurants and souvenir stalls around Yubaba’s bathhouse in Spirited Away. “We can consider many aspects of the shop even now — how excited the owner must have been when it opened,” he says. “How they harbored the hope it would be a hit. We can wonder what they gave out at the shop’s opening celebration.”

The deeply human focus of that analysis reflects Miyazaki’s approach to his art. Creating that detailed backstory enables him to imbue the shop with life when Chihiro and her parents see it. Whether it’s part of a derelict ghost town or a bustling resort for weary nature spirits, this building isn’t just a backdrop. It’s an essential part of the world Miyazaki is creating, a world inhabited by living characters who interact with their environment.

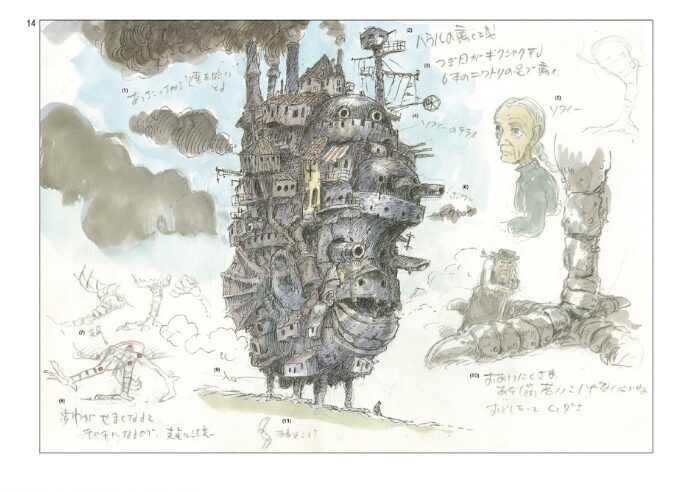

In addition to his learned explanations about architectural styles and history, Fujimori notes that the buildings in the Ghibli films are so carefully designed, they could easily be constructed in real life. He confesses that he wants to build the ramshackle, steampunk title structure in Howl’s Moving Castle: “At first glance, it looks like a complicated oddity that could only exist in fantasy, but you could actually build it if you tried.” Fujimori says he would have to use “the incredibly strong material called single-crystal iron,” but concedes, ”it would be difficult to make it walk or fly.”

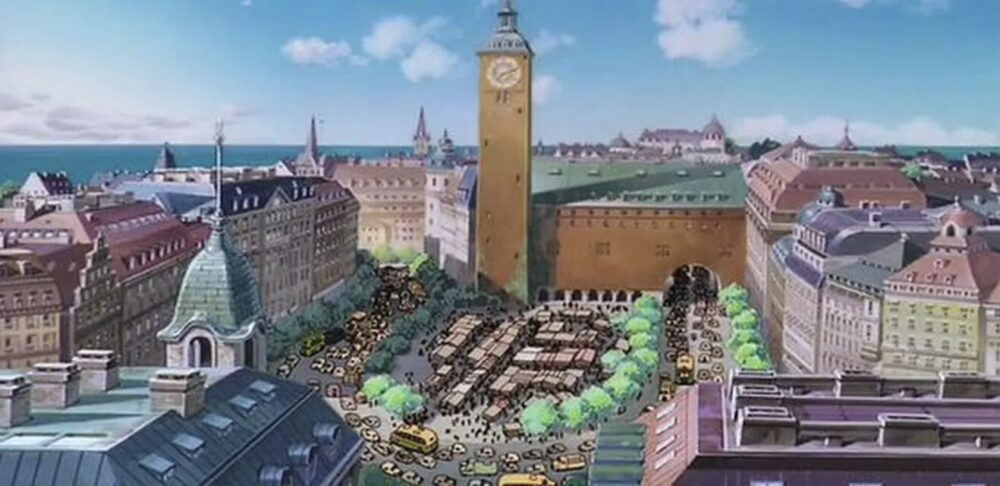

Miyazkai pokes gentle fun at the stylistic mishmash of the city where Kiki and Jiji move in Kiki’s Delivery Service. “This is how the Japanese imagine an old European city,” he comments. “There are elements of Naples, Lisbon, Stockholm, Paris and San Francisco all mixed in, so one side faces the Mediterranean while the other faces the Baltic Sea.”

The back-and-forth discussions also help the reader understand the details of architectural styles unfamiliar to Western readers. Fujimori explains that the Latin Quarter in Goro Miyazaki’s From Up on Poppy Hill is an example of the Giyōfū pseudo-Western construction style, modeled on public buildings that the first magistrate of the Yamagata region had erected as symbols of the modernization of Japan at the end of the 19th century. The clapboard walls, pedimented windows, elaborate staircases and what was once a gas-lit chandelier emerge when Shun, Umi and their friends clear the structure of decades of abandoned student projects.

Although Miyazaki clearly respects Fujimori’s work and has done extensive research in Japan and Europe, he irreverently says of his films, “The images are simply fabricated inside of me. That is how location scouting is for me as well, it’s basically all fabrication. I go to the locations not to investigate them but to decide how much I can lie about them.”

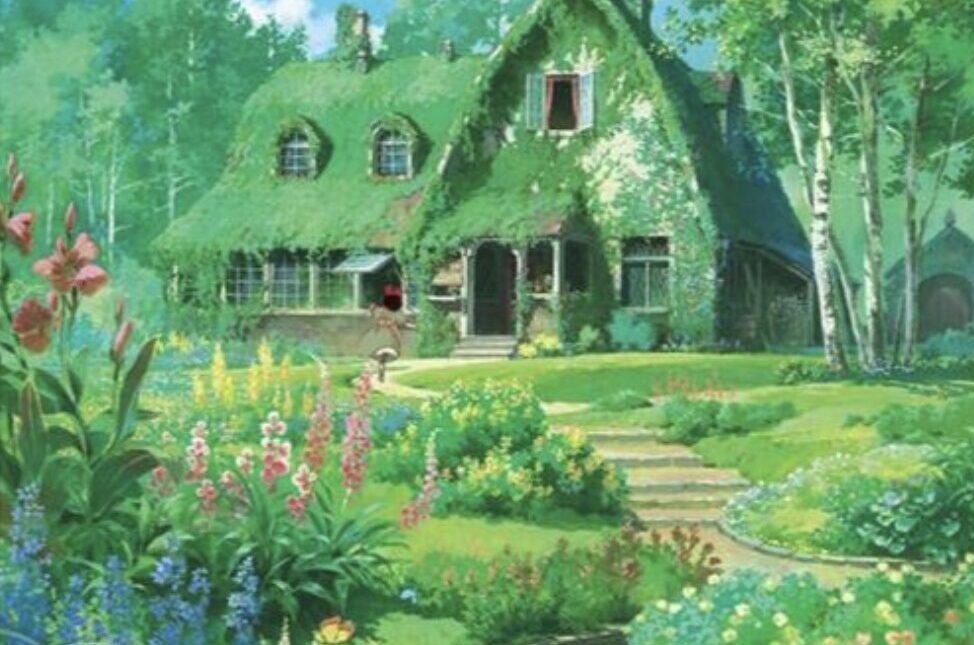

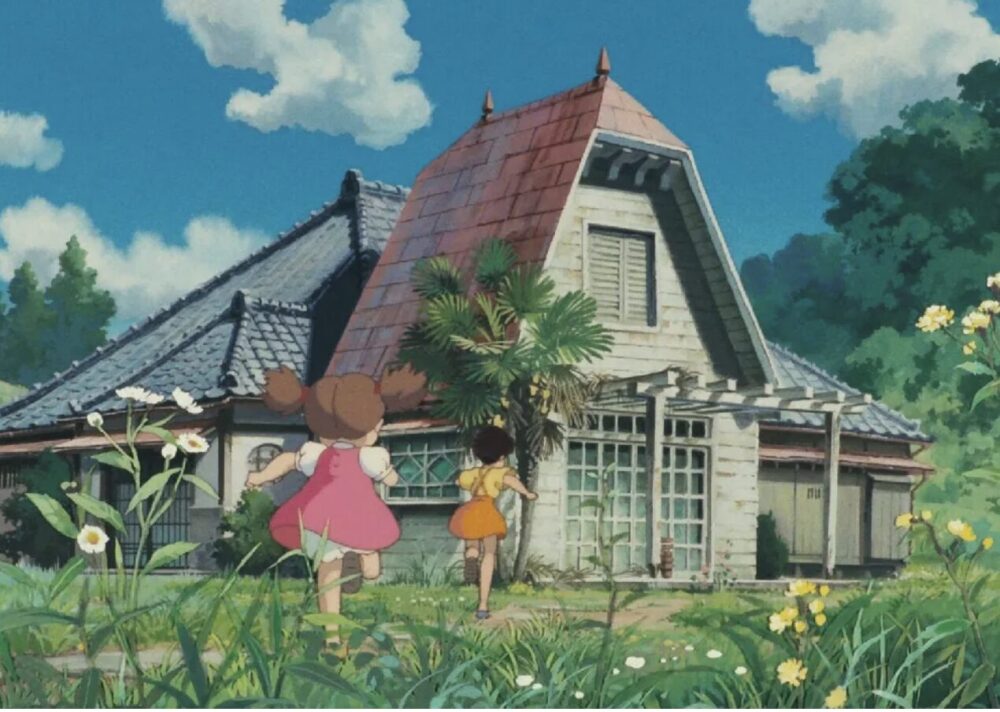

The building that receives the most attention is the slightly gone-to-seed house in the countryside that Mei, Satsuke and their father move to in Totoro. Fujimori describes it as “a somewhat fashionable office worker’s house from the Showa period (1926-1989).” He goes on to describe how the structure incorporates Japanese and Western elements and how the interior space would be configured.

Miyazaki replies, “When my brothers saw this house, they said, ‘What? You put our house in it?’ It was located in the Eifuku neighborhood of Suginami, Tokyo, but has long since been torn down. This is a memory of that house.”

Where People Want to Live

Fujimori discusses the details of the house — the roof, shutters, doors, tiles. But Miyazaki has the last word and once again stresses the human aspect of his vision. He says he wanted to “create a place people would want to live.” He recalls that when the staff saw the rushes for the film, no one commented on the animation:

“They would instead say, ‘I wish I lived there.’ [laughs] No one wants to lower their standard of living, but they would want to live in a place like this if they could. That feeling has fairly deep roots. With the water, trees and space, you think how lovely it must be to live there, connecting with kind neighbors — this desire seems to be innate in our hearts.”

The desire to live in harmony with nature during the four seasons of the year has been an essential theme of Japanese culture for centuries. Time and again, Miyazaki has combined traditional values with his artistic vision to create places where audience members, like the staff artists, wish they could live.

Studio Ghibli: Architecture in Animation [Viz: $35; 192 pages] by Terunobu Fujimori and Hayao Miyazaki is currently available online and in major bookstores.

“The images are simply fabricated inside of me. That is how location scouting is for me as well, it’s basically all fabrication. I go to the locations not to investigate them but to decide how much I can lie about them.”

— Director Hayao Miyazaki