Director, animator, screenwriter and animated film producer Karla Castañeda is probably the youngest and most talented director on the Mexican animation scene. A graduate in Communication Sciences from the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (ITESO), she made her first short film Jacinta in 2008, which in addition to winning the 2009 Ariel and the best animated short film awards at the international film festivals of Guadalajara, Cancun and Morelia (which earned her a direct pass to compete in the International Critics’ Week at Cannes 2009), she also received multiple international awards and was shortlisted to compete at the Oscars in 2009.

Castañeda followed this successful debut with La Noria (The Waterwheel), which won the Ariel in 2013 in addition to receiving various national and international awards, and earned her the appellation of “Most Promising Director” at the 1st Latina Short Festival in California in 2014.

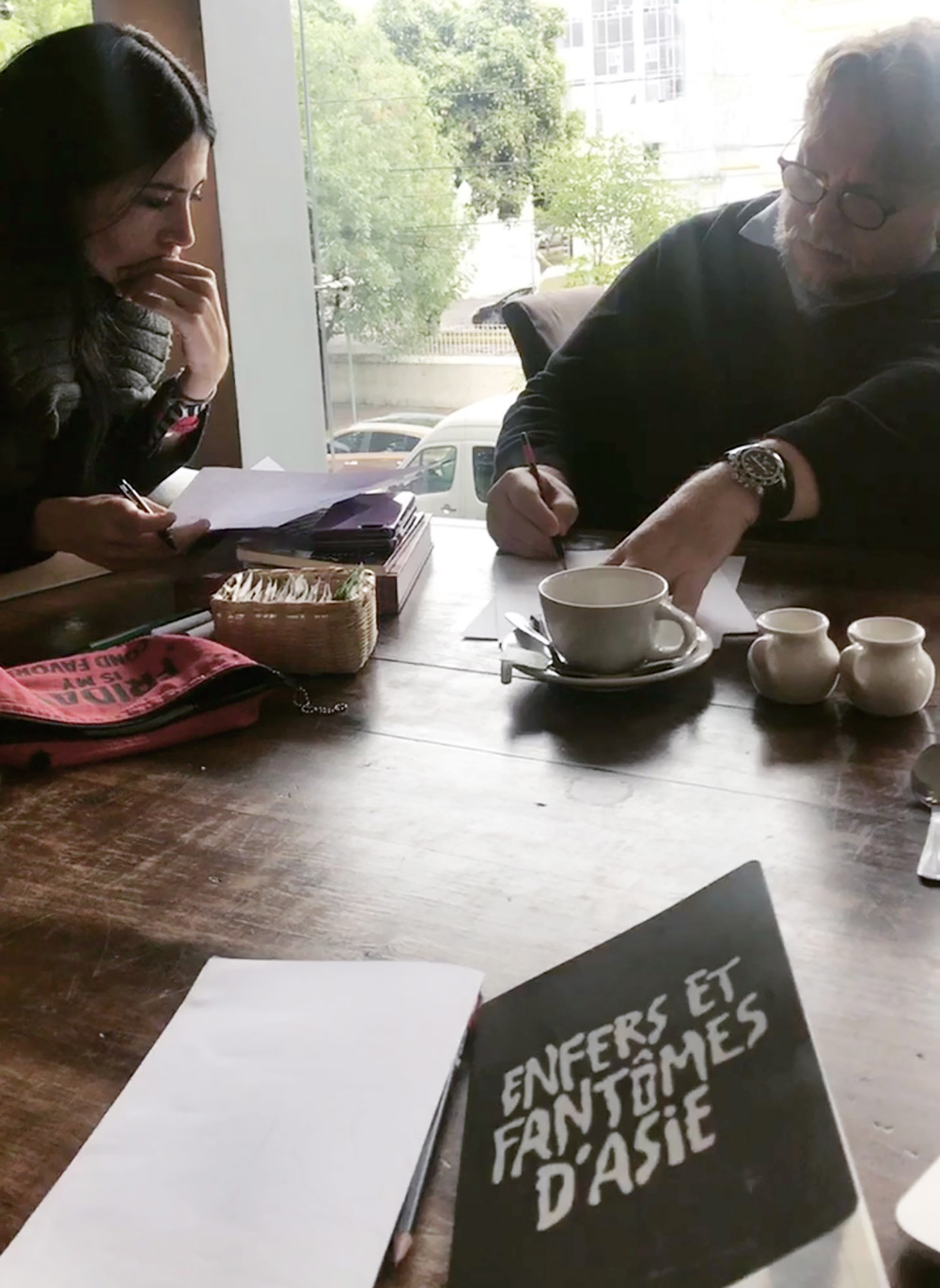

Now, Castañeda is working on the pre-production of her first feature film, which will be produced and co-written by Oscar-winning filmmaker Guillermo del Toro. The project is billed as the first feature-length stop-motion animation film produced in Mexico.

“I grew up in a town like Macondo, like Comala, where everything was magical realism, it seemed like a ghost town,” Castañeda recalls. The rising filmmaker appeals to the memories of her childhood to recreate stories that enriched the fantastic imagination that characterizes her work, resulting in interesting films whose narrative and visual content have captivated thousands of people around the world. Seasoned with excellent art design, Castañeda’s short films are unique due to their peculiar aesthetics, but it is through narratives full of symbolism, fantasy and emotive characters that she manages to stand out from other animated productions.

In her own words, making short films that put technique or aesthetics above the story has never been her goal, but rather telling stories that provoke emotions in her viewers — a goal that she has easily achieved. As loneliness, memory, loss and death are some of the recurring themes in her cinematography, Castañeda has had to give her characters the stature and strength necessary to be able to tell forceful stories. The characters’ merit is doubly plausible, having been achieved through animated stop-motion puppets, guided by the hand of Luis Téllez — one of the best Mexican animators. The filmmakers have achieved excellent results in their mission, creating works that shine for their empathy and universality.

“Guillermo del Toro always tells me that the structure is like the foundations of a building, if they are good it will be solid,” Castañeda notes.

Q&A with Karla Castañeda

Leon Alejandre Torres: It’s thought that every artist goes through two basic moments before deciding to turn his life towards art: the first is when the artist discovers works so captivating that they will make him adept at art, and the second is when he finds a work so sublime that he will decide to dedicate his life to create works of a similar nature. In your case, what were those moments?

Karla Castañeda: In my case, that first one was when I began to read; reading influenced me more than the visual aspect. When younger, I read classic tales, [like Alexander Pushkin’s The Squire’s Daughter]. Later I began to be passionate about Russian literature; Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol, Chekhov, Tolstoy, Borís Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, Bulgakov, Dostoyevsky (Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, The Brothers Karamazov). And little by little I liked to explore literature by country. I also like Latin American writers; Horacio Quiroga, Borges, Cortázar, Sabato, Adolfo Bioy Casares, García Márquez, Juan Rulfo, Roberto Bolaño, etc. In my head I had an imaginary world where I started to imagine what Úrsula Iguarán, Remedios the Beauty or [other characters] would be like … Then I started reading about everything. Now I am reading a British neurologist, Oliver Sacks, one of his phrases that I like most is: “Sometimes I thought I had lived at a certain distance from life itself.” I’m reading [his memoir] On the Move: A Life.

And the second moment happened because I really like to draw, make asymmetrical characters and play with giving life to each one of them, to tell a story, create their biography. But they didn’t move. I had them on paper, I had the ideas, images and characters, but everything was just in my head and notebooks. I wanted to do something with them. The idea of creating comics didn’t please me, although I confess that I read them and I admire them; Marjane Sartrapi, Gaiman, Nina Bunjevac, Igort, Paco Roca, etc. One of my great collections and passions are children’s picture books, as well as graphic narrative.

I did my thesis about a concern I had, stop-motion animation, and well I had to go to the studio where the models of Down to the Bone were assembled; I met René Castillo and Luis Téllez there. I also went to Rita Basulto and Juan José Medina’s studio and at that time they were finishing The Eighth Day of Creation. I was fascinated by the world of animation, and I would find my way of expression in it.

Is there a group of Mexican animation filmmakers that you admire or follow closely?

I admire Carlos Carrera a lot; my favorite Mexican animated short film is The Hero. I admire Luis Téllez; for me he is the best Mexican animator. And I closely follow almost everyone who is doing animation, whether stop-motion, 2D or 3D. I really like what Emilio Ramos does. I admire Jorge Gutiérrez a lot, not only on a professional level but for his generosity, his support for new generations as well as the example of his career.

Who are your main influences?

I really like Jan Švankmajer, The Brothers Quay, Sylvain Chomet, Regina Pessoa, Adam Elliot, Brad Bird, Tim Burton, Jérémy Clapin, Claude Barras, Hayao Miyazaki.

The characters that we find in your shorts are so universal and have such a projection that the public not only manages to easily identify with them, it also creates immediate empathy. How is it that you manage to give your characters so much presence and depth … Do you create their own soul or do you share part of yours?

I think it already comes implicitly when it comes out of me. Each one of my characters has something from my childhood, from what I suckled as a child, from my adolescence. I grew up in a town like Macondo, like Comala, where everything was magical realism, from eccentric tortilla makers to a man who rang the church´s bell at nights (but only a few could see him). In the streets I sometimes saw women with children, babies, donkeys and sheep, and minutes later, they all seemed to have been swallowed by the earth — they all disappeared and it looked like a ghost town, I only saw the sand on the houses, the aridity of the countryside.

Afterwards, I get to know each of my characters, I identify them with everything that has surrounded me, I think a lot about them and I observe and structure their history.

Having a multiple-award-winning short film like Jacinta, is this really useful to open doors in the national and international animation market?

It helps a lot. It is a cover letter — winning prizes speaks well of what you are doing. But the most important thing is to keep working, writing; challenge yourself in new projects, think about what you want and where you want to go.

Do you feel that your creative process has changed a lot from Jacinta through La Noria, Batallón 52 and your work with OQO Films?

Yes, with Jacinta everything was more innocent, to call it somehow, but I don’t think my creative process changed. I always start with ideas, with images and some link from me to the others — it’s like a labyrinth, a puzzle. I try to tell something that is narrative and ensure each object and character has a reason in the story, not just for decoration. I think there are many beautiful shorts (aesthetically or technically), but for me, the most important thing is to tell something. Now, if it’s possible to get both: better.

Batallón 52 was a different and rewarding experience, because I worked with people that you don’t choose, as in a personal short film project (where you form your work team). It is difficult because I generally work with very few people, and on that project there were many heads, many styles, they gave me the scripts, I had a set delivery time for each minute. But at the end of the day you learn many things from each of them, and they enrich you. It was a different technique, and I’m always looking to learn and grow.

With OQO, it was also very distinct. The stories were beautiful and thinking about children’s stories was very different. The creative process was challenging because the stories already existed, but I had complete freedom to adapt them and make changes to the characters. Another challenge was that you have to be softer when telling the story — same with the art, production design, characters, narrator, voiceover, etc. And finally the biggest challenge was time: in about a month we had to animate nine minutes at 12fps, and direct three sets with three animators each.

You have had the opportunity to work as a screenwriter, animator, director and producer — of all these, which is your favorite role and which do you enjoy the least?

I like them all, each one is different. I like all the processes, from writing, production design, directing; to start making a short film and watch it grow. I really like pre-production; it is very exciting to start working with talented people, come up with the models, objects, characters, see everything on paper until they become a reality, mount all this at the set, and place the cameras, lights, etc.

The animation part also excites me, seeing the characters act, bringing them to life. And the post-production part, working with the musician hand in hand, with the sound designer, the actors who interpret the voices, the color correction … Maybe the part I like the least is as a producer — the numbers.

Do you think there has been an evolution in your projects?

Yes. Now when I watch Jacinta, which was a short film from 2007, I see many technical errors. But at that time, you worked with what you had at hand, then you created everything from those materials. We made Jacinta with latex foam, now we work with silicone. In Jacinta, we didn’t use greenscreen, but in The Water Wheel we did, and we used 3D — that helped a lot to facilitate the processes, such as water, some background skies, etc.

But the most important thing is to learn along the way and avoid repeating mistakes you have made, in your next short film. It will always be a challenge to start a new project, a new story.

Can you tell us something about your current projects?

This year will be the premiere of my short film Night Song. It is a story that begins with a personal trace of a family tragedy, an event that has been happening throughout the country for years, and will include elements of magical realism. Regarding the characters in this short film, I wanted to experiment with interchangeable 3D printed faces and dragon skin bodies.

I also finished co-writing another two-minute short that will be ready by the end of this year. The idea came from the pandemic.

Currently, I am part of the art team for Pinocchio, a film directed by Guillermo del Toro.

How did you meet Guillermo del Toro?

I met him four years ago at the Annecy festival (France). It was very nice because he invited me to his masterclass in the front row, in which he presented the Trollhunters teaser. When we finished, he invited me to have a coffee — I couldn’t believe it. He told me that he liked Jacinta a lot. I also showed him The Water Wheel, and we talked about our new projects. We kept in touch and met several times in Guadalajara and also in Sitges and Barcelona. In some of those meetings we talked about a story very similar in theme that we had in mind.

After winning the Oscars with The Shape of Water, he gave three masterclasses in Guadalajara, and that week we talked about that story. It was a very emotional moment because he told me that if we co-wrote that story he would produce it. Then he officially announced it in one of his masterclasses. I spent several months thinking it was a dream, that one of the directors I most admire in the world would produce my first stop-motion feature film. At that time we were already co-writing.

How has it been working with him?

I am really enjoying the writing stage. It is very different to write a script for a short film than for a feature film; it’s challenging. My three shorts didn’t have dialogue, but the feature film does. It is a totally different adventure. Working with Guillermo in each session is a masterclass — in every aspect he has creativity, skill and an incredible vision. I really like to learn from someone who has come so far, and who apart from the fact that he is a scholar, has a generous, empathetic and always encouraging human side.

Can you tell us something about how the production of this ambitious project is going?

Guillermo always tells me that the structure is like the foundations of a building, if they are good it will be solid. He once told me something that stuck with me: “The great movies had something in common: more history and less plot.”

When I write I imagine things, and I can’t help but draw the characters and capture them. I love Guillermo’s method, where there is a deep reflection of each character and a construction of his “psyche” from the most intimate details of his biography, tastes, desires, frustrations, fears, etc. to understand his way of acting and react in the story. “Character is equal to action.”

What have been the biggest challenges you have faced?

The short films had different challenges at the level of synthesis and of telling stories completely with images without dialogue, but now it is going from short to longform. In the CIA (International Animation Center) “Taller del Chucho” working on Pinocchio, the challenge is that each department has to communicate and coordinate in order to homogenize all the work with what is being developed in Portland. I am very grateful to Guillermo for this opportunity; being part of a film where the world’s stop-motion elite is involved, to create a work with great beauty and heart.

What recommendations would you give this new generation of animators who love stop-motion and have been partly inspired by your short films, and by Luis Téllez and León Fernández?

We are living in a very interesting time where the technique is very accessible, whether in online tutorials, masterclasses (which last year and this one were very enriching, due to the pandemic) or directly with professionals, through social networks. So now the challenge for the new generations is to take advantage of this technique to find their own voice with meaningful and personal stories, because the great films in the world are not the ones with the best technique but rather the ones that make us connect with the sensitive fibers that make us humans.

—

Leon Alejandre Torres is an independent animator and screenwriter based in Mexico. He can be reached via Facebook @Stopmotionarte or email (stopmotionarte@gmail.com).

This interview has been edited for clarity of language.