***This article originally appeared in the April ’22 issue of Animation Magazine (No. 319), International Education & Career Guide supplement***

While pandemic restrictions have impacted undergrad education in many ways, educators at premier animation institutions have focused on making sure their key classes remain robust. They’ve responded by making the most of remote connections and hybrid teaching techniques to keep their students inspired.

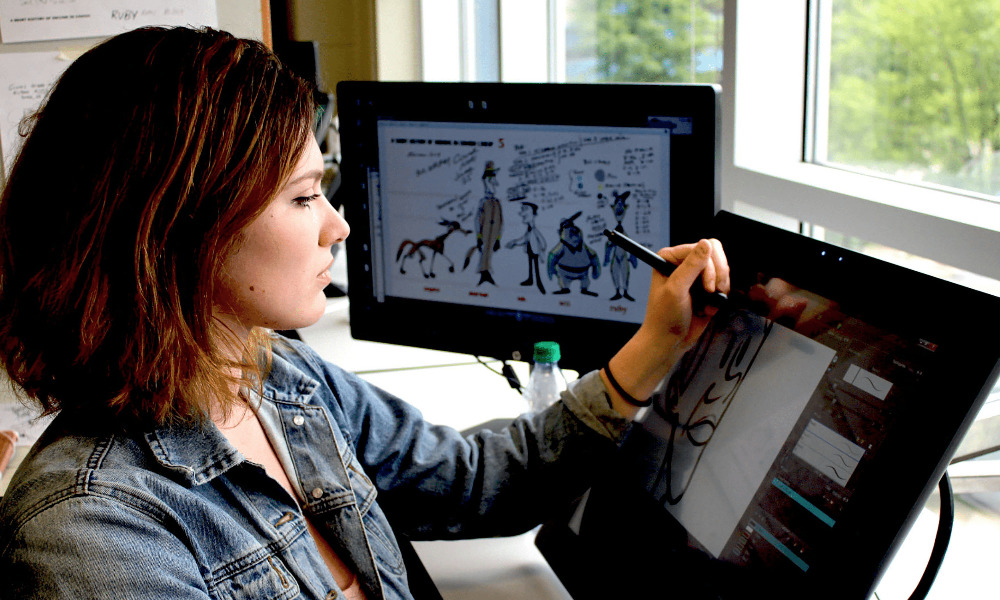

Digital Tools Class (Sheridan College)

Canada’s legendary animation college has evolved dramatically since its founding in 1967. It has grown physically — now occupying three campuses in the province of Ontario — and technically as well. Sheridan has built upon its traditional animation reputation by embracing digital technology to create a Digital Stream curriculum. To that end, students pursuing a Bachelor of Animation degree will find themselves in the required “Digital Tools” class taught by Mario Positano.

A Sheridan graduate himself, Positano has spent 26 years teaching and serving as a technical mentor on scores of student films. With each new crop of students, he takes a ‘ground zero’ approach. “I assume they don’t know anything. Some arrive with brilliant knowledge, while some struggle as artists taking a technical class.”

“Primarily I teach them Toon Boom Harmony both for hand-drawn animation and for a basic introduction to rigged animation. We also do some Premiere, After Effects,” he notes. Building on the basics of frame by frame drawn animation, Positano teaches students how to composite their animation with backgrounds and camera moves. “Then they’ll do a similar process with rigged animation, so they understand how to apply animation through a pipeline and end up with a finished scene,” he says.

Positano seeks to make his assignments fun — like animating dance moves and putting characters in unique settings. “Recently we did Western characters, which I loved,” says the enthusiastic professor. He even dressed up as a cowboy to lighten the mood.

Teaching via Zoom during the pandemic has challenged his young — and often shy — undergrads. “Some won’t come on camera, or speak up, or even turn their cameras on!” Fortunately, Positano explains, “Sheridan has a ‘desire to learn’ online platform called Slate, where they post their works-in-progress. Slate has a discussion board where they comment on each other’s work.”

Positano thinks that the online classes necessitated by the pandemic will help prepare his young students to collaborate in the distributed production models that continue to evolve. He explains, “When we return to in-person classes, it will be nice to hang onto what we learned does work.”

Given his extensive tenure teaching Digital Tools, Positano has a seasoned view of how imaging technology has evolved. “I find it fascinating that the trends are not consistent. When I started teaching, few students knew Photoshop. Then, around six years ago, I’d ask who knew Photoshop, and everyone’s hand went up. Now it’s back to just a handful again. Some students know Blender instead. It’s interesting that Sheridan has stayed true to its roots in life drawing and fine draftsmanship. People expect our students to be amazing artists, and they don’t disappoint.”

Storytelling in Blender (School of Visual Arts)

As the digital tools used in the animation industry continue to evolve, experimental animation teachers like James Bascara find new ways to bring them into the classroom. “Storytelling in Blender” is now being offered as an elective at New York City’s School of Visual Arts, centered on the freely downloadable, open-source program Blender.

“This is a fundamental course to get students used to the idea of 3D space,” explains Bascara, a 2011 SVA graduate himself. His interest in Blender mirrors his own journey into animation, since his SVA degree and professional career have been in illustration.

“I’m an editorial illustrator who’s self-taught in animation. Once I started making short films, I got into film festivals and that momentum organically led me to try Blender. I’ve also used it for illustration gigs as a way of modeling assets and basic shapes where I wanted dimensional work. I like the idea of having CGI mixed in with more hand-drawn stuff.”

That mix-and-match attitude is why the “Storytelling in Blender” class was co-created for the BFA Animation and Computer Art programs. Describing his eligible students, Bascara says, “I would welcome sophomores and up. I imagine if they have experience with Maya, they at least know the principles of creating images on this kind of platform. But the interface and nuances of Blender might be new to them.”

The Blender course work covers building and animating three-dimensional models and environments, as well as two-dimensional drawing, storyboarding, animating in 3D, compositing and video editing.

Bascara believes that many Blender class enrollees will arrive with a desire for world building. “The ability to create their worlds in 3D space might open up some other possibilities, and maybe even immerse them further into their worlds. Blender provides a good space to experiment. I do feel it’s part of the industry skill set now, and part of the visual language of 3D.”

As Bascara observes more and more illustrators and experimental artists embracing Blender and importing elements from disparate sources, he expects it will become more and more of a tool akin to Adobe’s suite. “It’s a great time for software in animation … and for art making in general,” he notes. “It’s all opened now — like Pandora’s box!”

Animation Pre-production (Ringling College of Art & Design)

If a single word could sum up the educational philosophy of Ringling, that word is, arguably, ‘collaboration.’ Pairs and trios of Ringling students regularly have been honorees at the Student Academy Awards, and the school’s curriculum has been specifically designed to foster creative relationships. A prime example of this is the class called “Animation Pre-production,” which is taught to students in the spring semester of their junior year. It’s the class where students form working teams and develop the ideas for what will become their senior thesis films.

“They actually have to sign up for this preproduction class as a team,” explains Paul Downs, a 2001 alum of the Sarasota, Florida college and 10-year faculty veteran. “On the first day of this class, they bring in four different ideas to pitch to the faculty. It’s a lot like the industry, where they present several iterations of a story.”

“As faculty, we’re responsible for helping them choose a film that they can finish. One of the unique parts of Ringling is that they must finish a film that’s approved by the entire faculty in order to graduate,” Downs remarks. “We put a time limit and a character limit on their film ideas. Students have giant dreams, but they quickly realize that they’re responsible for executing all of them.”

“I tell them I made a lot of mistakes when I animated at Ringling,” he adds. “So they see me as a former student.” But he has also animated at Blue Sky Studios, on franchises such as Ice Age and Rio, and he tries to bring his real-world experiences to bear. “I want them to know what to expect from the industry.”

Downs likens Ringling’s faculty critiques to dailies sessions, and the studio notes that students will handle in their careers. “They get used to receiving constructive criticism as well as learning how to ‘plus’ each other’s work. They can see how holistically everything works together.”

Ringling’s emphasis on collaboration was obviously tested by the pandemic restrictions on in-person classes. But, Downs asserts, “We didn’t put the brakes on when the pandemic hit. It was a short pivot to getting machines to people working from home. Teaching has been just as direct, because I’m able to draw remotely on the students’ frames, and they’re able to record and revisit faculty critiques. We’ll probably stick with the model of doing our full faculty critiques over Zoom.”

Whether the students work remotely or in-person, the ultimate goal of this linchpin Ringling class remains the same: When they arrive at senior year, they will be ready to begin production of their films on Day One.

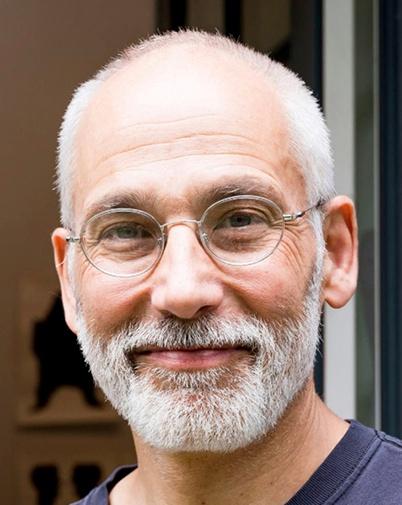

Senior Studio: Animation (Rhode Island School of Design)

Providence, Rhode Island has long been a destination for aspiring artists from around the world, and a key reason is the stellar reputation of its faculty. Notable among them is animation teacher Steven Subotnick, a 2017 Guggenheim Fellow who began teaching at RISD in 1994. Subotnick, who’s also taught at Harvard, has been teaching the “Senior Studio: Animation” course at RISD since 2010.

“The senior degree project course has been in existence since about 1983,” notes Subotnick, whose own highly personal, experimental animated films have been featured at film festivals worldwide. Subotnick co-teaches the full-year course alongside RISD teacher Amy Kravitz, sharing responsibilities for developing the syllabus as well as critiques of individual student films.

The “Senior Studio: Animation” course requires that students develop, design, animate, direct and produce their projects independently. They receive weekly individual guidance from instructors, along with two critiques by established professionals from the world animation community. “There is no pre-production class for this course,” says Subotnick. “Nor do the students need our approval for their projects.”

Even a cursory glance at past senior projects reveals a diverse range of themes and techniques — from highly graphic hand animation to full 3D.

“Digital technology is integrated with physical media in our department,” Subotnick explains. “There are students who work completely digitally, but many students mix digital techniques with physical media.” For example, he notes, “We’ve remained committed to supporting stop-motion animation.”

The one student/one film approach of this class still faced challenges during COVID times. Subotnick recalls, “The school was quite good about pivoting to remote teaching, and it worked well. Normally, we take the students to the Ottawa International Animation Festival in Canada, but of course we couldn’t do that. Yet there were some silver linings. For example, we found that we could invite more guests to speak to the students because there was no travel involved. And our culmination show at the end of the year worked very well online, so this year we intend to have both an in-person and an online version of the show.”

While RISD is admired for its fine arts reputation, Subotnick notes, “Our graduates work in many areas of the animation field, including features, TV series, commercials, special effects and games. Some start their own studios or become fine artists or teachers. It is important to note that ours is an undergraduate program, so our students are still young when they graduate!”

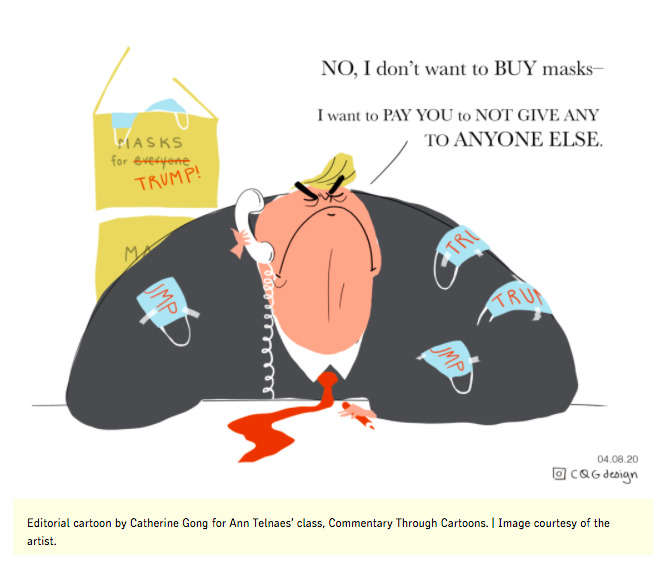

Commentary Through Cartoons (California Institute of the Arts)

While the prestigious animation programs at CalArts are known for honing students’ film production prowess, they also offer some tasty ‘side dishes’ on the menu of classes. One striking example at CalArts’ Valencia, California campus is “Commentary Through Cartoons,” taught by the Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post editorial cartoonist Ann Telnaes.

Telnaes, who graduated from the CalArts Character Animation program, first taught “Commentary Through Cartoons” in 2020. Her single semester elective course is open to Character Animation students at all levels, but Telnaes also has the discretion to accept students from other CalArts programs. “I believe there is one Art major in the class this year,” she notes.

The course requires no prerequisites, and Telnaes is open to having her students create cartoons in the forms of graphic essays or animation, as well as single- or multi-panel drawings. This openness reflects her own diverse background — Telnaes has used a variety of media in her work and has published three books. What makes her attuned to students in CalArts programs is that she also worked for several years as a designer for Walt Disney Imagineering, and has animated for studios in Los Angeles, New York, London and Taiwan.

“In the first class I ask them to get in the habit — if they’re not doing so already — of reading or listening to the news daily. They can get their news online, in print, by radio or TV. The only rule is it should be a legitimate news source — not links through their social media feeds. I discovered in my 2020 class that several students were reading and sharing so-called news items without verifying where these stories came from. If they find something through social media, they have to back it up from a legitimate news site.”

Telnaes’ class also includes the history of American editorial cartoons. “I include images which would be considered inappropriate today, which shows that context is important.”

One context that’s notable for Telnaes is the rise of female students at CalArts — including 10 of her 13 students in 2020. Their standout cartoons garnered recognition by the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, and one was featured in The Boston Globe. Telnaes may be only the second female cartoonist honored with a Pulitzer, but with classes like hers, she likely won’t be the last.