If there’s a technology du jour in the growing trend of virtual production, it’s LED volumes. Studio walls constructed from panels of light emitting diodes are key elements of today’s XR (extended reality) stages, where hits like Disney+’s The Mandalorian are made. Increasingly, schools are integrating LED volumes with technologies like camera tracking, performance capture and real-time game engines — making the creation of in-camera visual effects more accessible to students than ever before. And each school is forging a distinct path.

“Introduction to Virtual Production”

Taught by Sang-Jin Bae

New York University

The recent announcement of a Martin Scorsese Virtual Production Center – and a Virtual Production Master’s degree — are just the latest indicators of NYU’s embrace of high-tech filmmaking at its Tisch School of the Arts.

Although the Scorsese Center and MFA are still in development, Tisch has been offering a Virtual Production class for three years. Teacher Sang-Jin Bae developed the syllabus with Rosanne Limoncelli, senior director of film technologies. As she explains, “It’s a combination of live-action, animation and visual effects. Even during COVID, Sang was running this class.”

The lockdown challenged them to develop a remote collaboration approach that continues today. “By design, we’re keeping it remote,” says Bae. “We’ve had students from China, the Middle East and the West Coast. It’s a global class that we’re building on.”

Through Visual Effects Oscar winner Rob Legato, Bae and Limoncelli met Noah Kadner of the Virtual Company, whose California-based LED volume was used for NYU’s class. Since remote collaboration is increasingly part of virtual production, Bae believes today’s students need to learn to communicate efficiently that way. “When we have a shoot, the stress is as equal as it is being on set.”

Typically, 20 students are grouped into teams of four to six and make two-minute shorts utilizing the LED Volume. One striking result of this approach is New Frontier, made by graduate and undergrad students. It shows how period pieces, usually prohibitive on student budgets, are facilitated by virtual production.

About a quarter of students are writers and directors, and Bae notes, “No computer experience is required. We’re teaching it in Unreal. They’re learning to visualize their stories without knowing VFX software. It’s an easy entrance.”

Limoncelli envisions growing opportunities for experienced NYU grads as virtual production proliferates. “There’s lots of jobs, and not enough people yet.”

“Collaborative Experiences in Film and Acting”

Taught by multiple instructors, overseen by Jud Estes

Savannah College of Art and Design

With LED walls installed on XR stages at its Georgia campuses in both Savannah and Atlanta, SCAD is fully committing to teaching virtual production. According to associate dean Jud Estes, “We’re the only school in the country that has two of these volumes at this scale, solely for students use. Both of our stages are 40-feet wide, 20-feet deep and about 18-feet high, and we have ceilings made of approximately 600 LED panels that are about 1.5-feet square. We can get almost a 180-degree pan from one end to the other.”

But the enduring challenge comes down to building teams of teachers with relevant expertise, believes Estes, a digital post pro whose credits include Blue Sky Studios. “We’re just beginning to create our curriculum because it is so new.”

“It’s almost a throwback to the old studio system where everybody’s on set at the same time working on a shot. The actors can now see the artwork in real time and react to it. I call these ‘living composites.’ It’s rewriting production pipelines,” says Estes. “We want to make sure our technology will be exactly what they’ll use in the industry. They’ll move from school to the set as seamlessly as possible.”

“Virtual Production”

Taught by Emre Okten, Sean Bouchard and John Brennan

University of Southern California

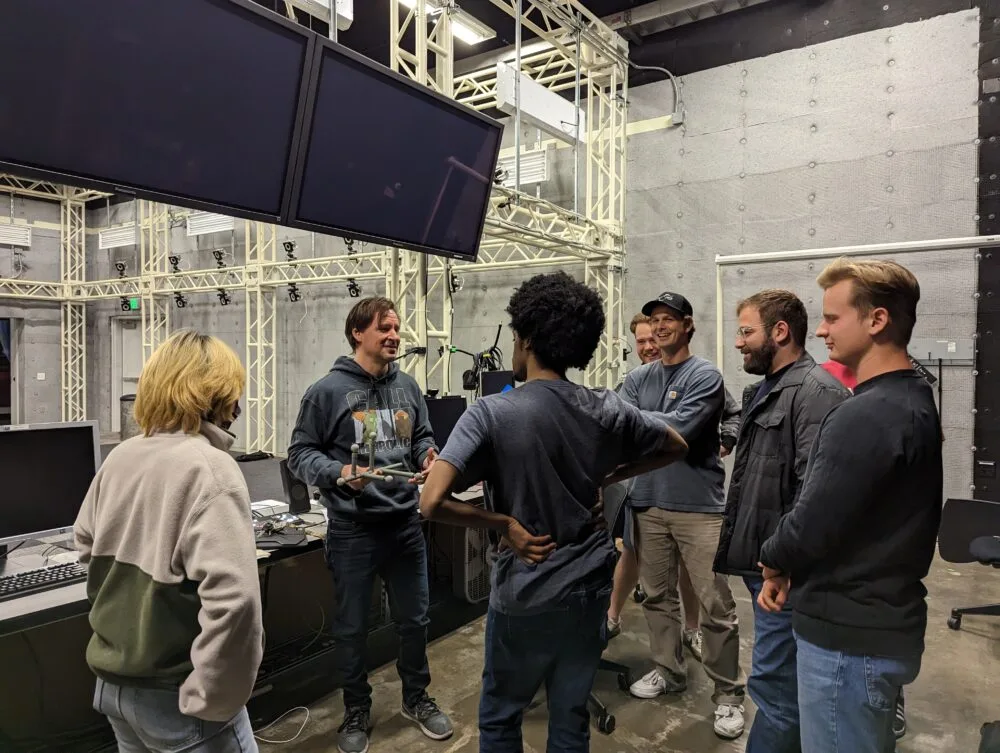

USC’s School of Cinematic Arts has long been known for its investments in imaging technology, and its new Sony virtual production studio is just the most recent example. Creating a teaching system to utilize these tools is now the goal. Last semester, USC introduced its first Virtual Production class, and this term has brought together a teaching trio with backgrounds in real-time CG filmmaking, interactive games and motion capture.

“We’re attracting students from different divisions to collaborate” says co-teacher Emre Okten, who previously won a Student Academy Award for his USC animated thesis, Two. “Virtual Production is such a collaborative area.”

“That’s fundamental to this kind of filmmaking,” notes co-teacher Sean Bouchard, who teaches real-time gaming. “We’ve got 15 students, and we’re figuring out how to introduce them to the tools and practices behind different technologies. They’re learning to use the LED wall not just as a backdrop, but also as a light source, and how to use the combination of performance capture and in-engine virtual effects to capture in-camera visual effects.”

Their students arrive with different filmmaking and interactive literacies, notes John Brennan, a USC mocap teacher and a VES Award winner for virtual cinematography in Disney’s 2016 version of The Jungle Book. “Yet there are many things related to virtual production that nobody has been taught yet. Our syllabus looks like a production schedule.”

“On Day One, they dressed up in mocap suits,” recalls Bouchard. “We had them learning how to use the real time engine interfaces, scout virtual locations and import assets from online stores. It’s organized around stories they want to tell.”

The teachers take turns leading different parts of the class, reflecting how interdisciplinary virtual production really is. “I’d like to think this little community we’ve started is just beginning,” says Okten. “It’s not hard to imagine that in ten years, ‘virtual production’ will just be called production.”

“Virtual Cinematography”

Taught by Jeasy Sehgal

Georgia State University

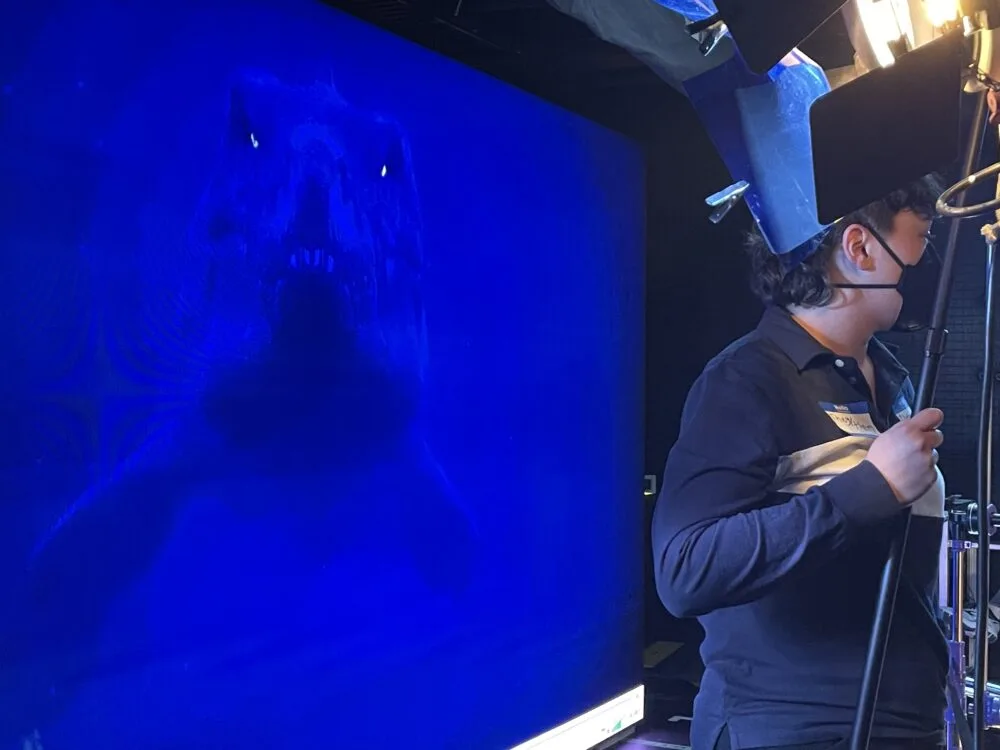

This year marks the start of a new master’s program in Virtual Production at Georgia State’s Creative Media Industries Institute. Spearheading CMII’s new program in Atlanta is Jeasy Sehgal, who’s teaching the program’s “Virtual Cinematography” course.

Designed for 15 students, this class is structured for students to produce multiple 2-3 minute short films. As Sehgal explains, “Critical thinking methodologies are an important part, along with working in the volume, getting in-camera VFX and having real actors composited with virtual ones. My personal research background is based around creating digital humans, so I’ll strive to get as much photorealism in these projects as possible.”

“We’re working with the Real Illusion Character Creator and iClone, where we can create realistic digital human and incorporate industry-standard performance-capture tools. We’re directly live streaming into Unreal while using a live camera to record against LED screens.”

“When we talk about the key tools in Virtual Cinematography, there isn’t one right answer,” Sehgal observes. A key goal is for students to understand the technical aspirations of storytelling. “My class is focused on content creation. They’ll design individual projects, but also work as group, potentially collaborating with film students who are specializing in traditional cinematography. We want to lower the barriers of entry to storytelling and have them come up with wild ideas. Every student comes up with a zombie story sooner or later!”

“Advanced Unreal Engine for Filmmaking”

Taught by Bennett Bellot (in collaboration with Richard Holland and Jurg Walther)

Chapman University

In Orange, California, Chapman’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts took a page from Hollywood’s playbook and installed a nine-foot LED wall back in 2021. One of the prime movers behind this was Game Development teacher Bennett Bellot, who created the “Unreal for Filmmaking” course that has now expanded beyond his original goal of creating a pipeline for digital art.

The 12-student advanced production course, that Bellot now teaches, is designed to help students bring their Unreal skills onto Chapman’s LED stage and create broadcast-ready scenes. “We have a cross-pollination with students learning lighting and cinematography,” he explains. “Most of my students come out of animation or visual effects, so they’ve done almost everything in front of a computer screen. They hardly ever get on a stage.”

But they are now, jumping into what Bellot calls “the deep end of the pool.” For example, they’ll learn how to create an image from Unreal on a stage and recreate it in camera. “There are LED lights that connect directly to Unreal so that if the camera spins, they’ll change to reflect whatever light they should be showing. The best part is that they can see it in real time. They can show it in Unreal to a cinematographer who’s never seen it before — and then they can make real-time changes. Everyone is getting hands-on experience.”

After 15 years focused on teaching Games, Bellot now sees growing opportunities for virtual production students who are learning to become more ‘generalists’ than ‘specialists.’ “I tell them they’re training for a job that doesn’t have a name yet.”