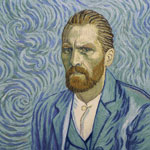

Billed as the world’s first fully oil-painted animated feature film, Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s Loving Vincent is a stunning achievement and a marvel to behold.

“We cannot speak other than by our paintings,” wrote the beloved Dutch artist Vincent Van Gogh in his final letter before his death. Husband-and-wife team Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman have taken the painter’s words to heart and created a stunning movie that brings his paintings to life, with the aid of 125 painters from all over the world.

The journey of this acclaimed feature film, Loving Vincent, which won the top prize at Annecy this year and will be released by Good Deed Ent. in the U.S. in September, began almost ten years ago when Kobiela (Little Postman, The Flying Machine) set out to make an animated short about Van Gogh. As co-director Welchman explains during a recent phone interview, she had studied fine art and was always intrigued by the life and work of the Dutch painter. “She had been re-reading his letters and wanted to paint a seven-minute short based on his life herself,” recalls Welchman. “When I moved in with her, I started to read about him as well and was able to persuade Dorota to do a feature-length movie instead of a short.”

“I was 30 when I first came up with the idea to do this project, around the same age Vincent was when he started to paint,” notes Kobiela. “More than his paintings, which I do love, it was the example of how Vincent lived that inspired me. I have battled with depression all my life, and I was inspired by how strong he was in picking himself up from similarly terrible life setbacks as a young man, and finding through art, a way to bring beauty to the world.”

Welchman, who is based in Poland and has produced several well-received animated projects such as the Oscar-winning short Peter & the Wolf (2006) and The Flying Machine (2011), says he became absolutely obsessed with Van Gogh’s enigmatic life and phenomenal achievements. “He had failed at four careers by the time he was 28,” he elaborates. “He was written off by his family as a no-hoper. But then he became a self-taught artist without any real artistic background and was able to create a body of work that mesmerized the world in only ten years.”

Soon, Welchman convinced Kobiela that it would be impossible for her to work on such an ambitious project alone. “We did a quick calculation, and it would take her 81 years to paint the film,” says the film’s writer-director. “So, we decided to invite painters from around the world to audition for the film. We had over 5,000 applications, and out of that we held auditions. The ones who passed the tests, were put in an intensive, 180-hour animation course, and then, we had 125 people who joined our production as painters.”

Art Isn’t Easy

Of course, the directors had their share of concerns about their gigantic undertaking. “I was worried about hiring these painters who had not worked on an animated project before,” he notes. “It’s hard to stop animators from fighting each other let alone these artists who were used to painting on their own. And they had to learn to paint in this specific style. We thought that was going to be problematic. But the funny thing is that that wasn’t the toughest challenge. I thought painting 65,000 oil frames on 103 cm by 60 cm (about 3.4 feet by 2 feet) canvases was going to be difficult, but persuading people to give us the money we needed was tougher. Fortunately, we were able to raise the $5.5 million needed for the project—which is probably just the cost of the title sequence for a Star Wars movie… We were, without a doubt, coming up with the slowest method of making a feature film ever devised.”

Kobiela started the first draft of the feature film in 2011, and Welchman joined the project a year later. After making the concept trailer, they tried various animation techniques to evoke the fluid, familiar style perfected by the Dutch master. “We practiced with glass animation, then tried a mixture of computer animation and painted animation. We were constantly writing and testing the animation to bring Van Gogh’s paintings to life in the most vivid way possible.”

Imitations of Life

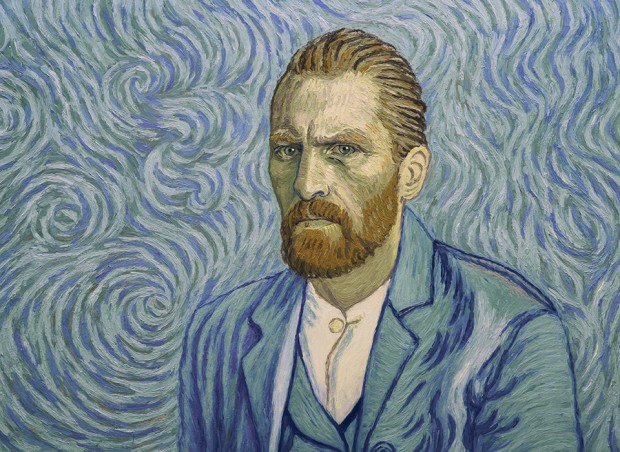

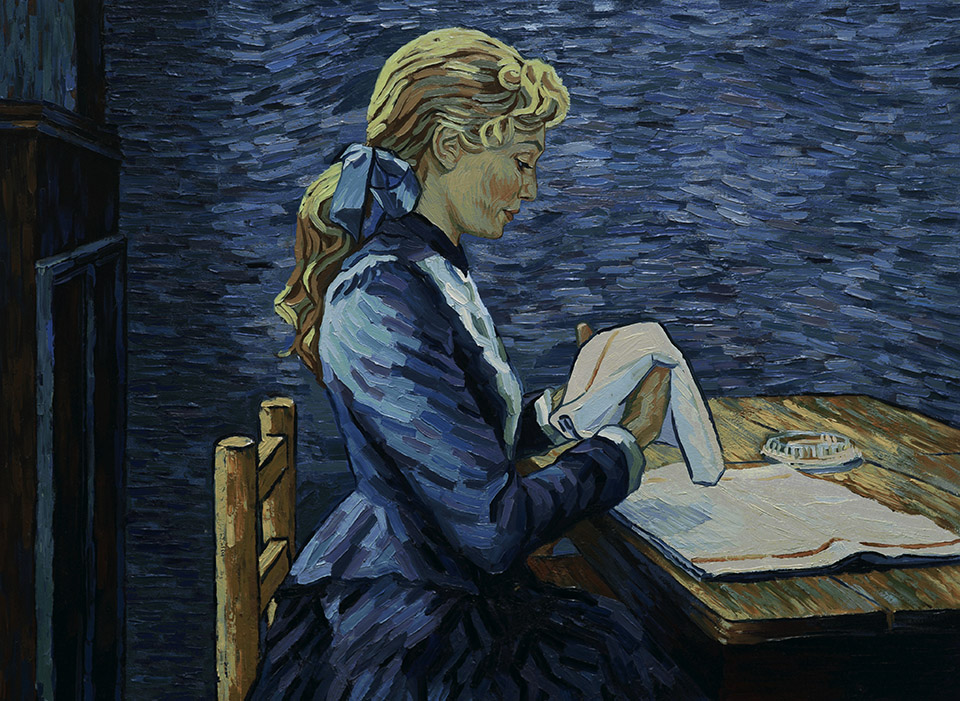

With the help of head of painting Piotr Dominiak, vfx supervisor Lukasz Mackiewicz and head of production Tomek Wochniak, the team came up with the plan to shoot the project first as a live-action film in London. Using actors such as Douglas Booth (playing Armand Roulin), Eleanor Tomlinson (Adeline Ravoux), Jerome Flynn (Dr. Gachet), Saoirse Ronan (Marguerite Gachet), Chris O’Dowd (Postman Joseph Roulin) and Aidan Turner (The Boatman), the directors re-enacted the painter’s final weeks to offer clues about the mystery of his death.

“We were lucky because Dorota had a wide range of experiences in visual effects, design, editing and animation,” says Welchman. “She knows all the different computer programs. I had a lot of experience in stop-motion projects, so together we came up with a combination of the way we produced stop-motion film, traditional animation and visual effects.”

Welchman and his team began the process by creating a simple animatic and previs for each of the sequences. “We had to spend a year re-imagining the paintings to bring them to life,” says the director. “The live-action scenes were done with green-screen about 80 percent of the time, and on set about 20 percent. The previs helped us a lot because Van Gogh’s paintings don’t usually jive with physical reality. You can’t build them and they defy the laws of physics. That’s why we had to map everything out and define the environments with computers, just like we were directing a vfx-heavy film. Then, we composited with 2D and CG animation. After all of that, our team of 125 artists started to hand paint the footage frame by frame.”

The team used Maya for the 3D animation, After Effects and Photoshop, as well as Nuke for the on-set composite work. They also incorporated Dragonframe software for the animation. The production team was able to use high-quality digital copies of the art with the cooperation of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. “We wanted to use their expertise not only with the script, but the painting technique as well,” explains Welchman. “They get a thousand requests a day, so it took us about a year to hear back, but we were able to gain their trust and they gave us access to the experts and to the paintings. The Dutch premiere will be held at the museum on October 5.”

A Man of Mystery

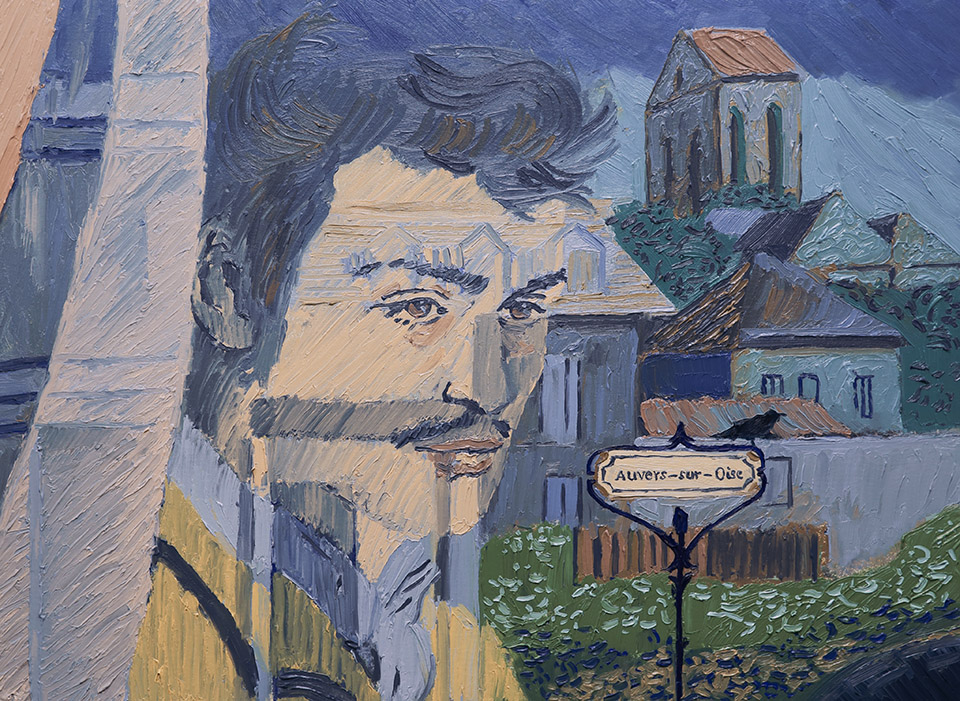

Many have wondered why Kobiela and Welchman took an unconventional approach to the painter’s life, framing the story as a quasi-mystery—an investigation into the reasons behind his death. “We did nine versions of the script,” says Welchman. “Dorota’s first script for the short was a very sensual film. We always had these questions about his final weeks, what was he feeling during this time. Our big question was why. He had been much more depressed in his life before. There were many reasons that he was having a more positive time. He had just sold his first painting for a proper sum of money and he had got great reviews. Other painters were tipping him to be the next big star. In addition, his brother Theo had just name his son after Vincent.”

Around the same time, a biography of the painter by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith put forward the theory that perhaps Van Gogh didn’t commit suicide and he was accidentally shot by some teenage boys. “Dorota and I thought that by looking at different and conflicting theories on his death we could understand more about his life. There’s drama that comes out of that conflict,” says Welchman. “We also watch a lot of film noir, so the approach was natural for us.”

So how do they see the death of their enigmatic subject? “We have different opinions,” says the director. “Dorota thinks he killed himself because of his brother, because he felt he had been a burden to him for too long. I am more open to the theory that he might have been accidentally shot. We have been arguing about who’s right for a few years now!”

As the film’s producers await Loving Vincent’s release worldwide this fall, they are pleased that their labor of love will spark more interest in the life and art of the tortured artist. Welchman also hopes that their incredible technique will be embraced by more directors. “I am in love with our method of filmmaking,” he exclaims. “I hope other people will want to direct in this style. It’s a shame to spend so much brain and heart power to set up this style and not have others follow it as well.”

He also points out that Van Gogh’s life continues to be a source of inspiration for him and his wife. “During the production, there were times when we worked 14 hours a day, seven days a week, and I felt quite miserable,” he recalls. “But then, I’d tell myself, ‘Come on, Hugh, pull yourself together!’ Look at what Vincent did. He worked so hard and had so many things against him. There’s a reason he is seen as one of the greatest artists of all time. He had this amazing, intense passion for life.”

Kobiela agrees, “We only decided to take the risk of making the world’s first fully painted feature film because of how much people around the world are already loving Vincent. I hope this film will inspire audiences to find out more about Vincent, read his letters, and see his paintings in the flesh. I want everyone to be Loving Vincent.”

Good Deed Entertainment will release Loving Vincent in the U.S. on September 22. The film begins its European run in October.